I’m Feeling Lucky: A Eulogy

Maya Man

It feels impossible to remember precisely the first time I encountered I’m Feeling Lucky. She had a unique presence, not only in my life, but in the lives of many. The kind that makes it feel impossible to recall life without her. It’s as if she’s always been with you, there for you when you need her.

Which is why, it is with disbelief and a heavy heart that I appear in front of you on your screen today to give my final words of goodbye and honor her long legacy.

1998: A star is born

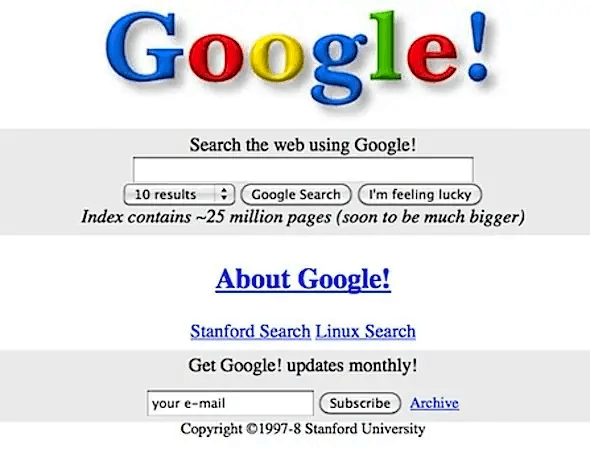

Born along with the very first publication of the google.com home page to the world wide web, I’m Feeling Lucky was, from the beginning, destined for greatness. She came online in 1998 as an <input type="submit" /> HTML tag type of button next to one of the most famous buttons in the history of online buttons: Google Search.

Sitting humbly to the right of her widely celebrated counterpart, I’m Feeling Lucky explicitly privileged feeling over function. Unlike the Google Search button, I’m Feeling Lucky enticed those searching to take a chance. While typing your query into the search bar and clicking the Google Search button would bring up a list of webpages you might be looking for, I’m Feeling Lucky teleported you directly to the first webpage listed in that results list, as calculated by the Google-patented PageRank algorithm. Ostensibly, she took you to the best result, the one that Google knew you wanted to see. When Google deployed the very first version of its website, I’m Feeling Lucky acted as a wink to its competitors. The implication was clear: We know, better than anyone else in the world, what you are looking for.

She could have been named something more literal. Something more, as one might say today, “user friendly.” Instead, I’m Feeling Lucky leaned into ambiguity. Embedded in the world of early Silicon Valley engineer-designed interfaces, she brought a dose of playfulness to an otherwise bare-bones webpage. She boasted an air of mystery, inviting users to click around and find out. From just below your query, she would gaze up and practically coo, “let’s get out of here.” And with a click of her button, you would.

If the Google results page represented all of the fish in the sea, I’m Feeling Lucky functioned like a blind date with a website. That kind of unexpected encounter used to be my favorite part of the internet. Logging onto my parent’s Macbook in our kitchen in suburban Pennsylvania, I felt a sense of potential every time I opened the browser. Websites, at that time, ruled the internet. In the 2004 blog post, “Websites Are The Art of Our Times,” artist Miltos Manetas points out, “‘Things’ in the Internet exist in a specific location, while in magazines and on TV contents are mostly bullets of information.” During this era, websites were nodes in a network that enabled exploration rather than singular, monolithic “platforms” designed to keep you in place.

2007: Real People

I’m Feeling Lucky led a relatively quiet life. Despite her prominent placement on the world’s most visited website, she received little attention from the media during her early years.

A piece of unusually prominent press coverage came in 2007, when Marissa Mayer, VP of Google Search at the time, answered Marketplace’s enquiries around I’m Feeling Lucky’s continued existence. Mayer declared that the button symbolized Google’s dedication to its purpose beyond profit: “You know Larry and Sergey had the view, and I certainly share it, that it’s possible just to become too dry, too corporate, too much about making money.” She went on to emphasize that I’m Feeling Lucky reminds users that those working at Google have a personality, interests, and are “real.”

Around this time, “realness” became a virtue technology companies strove to maintain as they mutated into exceedingly commercial entities. During I’m Feeling Lucky’s tween years, the internet began accelerating into the version of itself we are most familiar with today. In 2007, Apple released the first iPhone. Within the six year span of 2004 to 2010, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram all launched to the public, quickly amassing “users.” The internet became “read/write” even for those with very little technical knowledge. On these new platforms, the public gained the ability to both consume and produce media. You no longer simply visited people online, you friended, followed, and subscribed to them.

In the Marketplace interview, which includes quotes from both Mayer and Google co-founder Sergey Brin, you can feel, through the interviewer’s questioning, the mounting anxiety regarding Google’s privacy-breaching, profit-making methodology. Although Mayer estimates that less than 1% of searches route through I’m Feeling Lucky, Marketplace calculates that the button still might cost Google roughly 110 million dollars a year. I’m Feeling Lucky allowed people to automatically circumvent the Search results page, where Google is able to make a large sum of their profit through ad placement, and go directly to a website. Yet, in defiance of her quickly changing surrounding world, I’m Feeling Lucky remained front and center on google.com. She was a relic of Google’s desire to appear to be keeping it “real.”

Google is very protective of what appears on its homepage. Visited by millions of people each day, Google was seen, for a long time, as the front door to the internet. Allowing I’m Feeling Lucky to remain on the homepage signaled a sign of respect for the quirky early days of both Google and the internet. But that respect would prove short-lived.

2010: Soft R.I.P

In 2010, Google killed I’m Feeling Lucky. What afterwards stood in her place on google.com was merely a shell of her former self—a perverse memorial to her past life. To hover over the I’m Feeling Lucky imposter was to engage in a kind of Google roulette: adjectives flashed across the screen — I’m Feeling… “Trendy,” “Artistic,” “Doodley.” Rather than portalling you to a new location on the internet, clicking on one of these options would take you to a related page within the Google universe, such as Google Trends, Google Arts & Culture, or Google Doodles.

In other words, the button trapped you in place, a crushing feeling familiar to anyone online today. It mirrored what happens when you click a link on Instagram, desiring to visit somewhere else on the internet, but instead being held hostage in an in-Instagram browser. Over the course of I’m Feeling Lucky’s short life, she witnessed the internet’s evolution from open world terrain into a set of walled gardens. Software used to be about taking you places, but “user experiences” are now programmed to keep you in place.

2023: What remains

Understandably, there are many who still believe that I’m Feeling Lucky lives on today. It’s true that she still appears as a clickable option under the results that pop up automatically after you begin typing in the Google Search bar. But she remains buried under layers of interface. Because of these post-mortem design choices, we are not able to access her in her faithful form. As much as we might want her back with us, we must accept that her time has passed.

In her seminal essay A Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway, notes that “myth and tool mutually constitute each other.” The button as a tool has morphed over time. At this moment, I wonder how the posthumous mythology of I’m Feeling Lucky can continue to inform our relationship to the internet, even after her death.

Luck, as defined by the Cambridge Dictionary, means “the force that causes things, especially good things, to happen to you by chance and not as a result of your own efforts or abilities.” On a six year old YouTube video discussing I’m Feeling Lucky, user @lomasshaun8709 comments, “Google as nothing to do with Luck, its a computer.” This comment shocked me. Maybe Google has little to do with luck these days, but I’ve always believed that computers and luck are intrinsically intertwined.

![@lomasshaun8709 Youtube comment. [A screengrab of the comment referenced above.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fxq10wb7ogoji%2F5xDYo1cqhGxoRJfW7MmDsL%2Ff13171d9e2529771023110b091afebe4%2FScreenshot_2024-03-06_at_2.04.06_PM.png&w=3840&q=75)

Vera Molnár, pioneer of computer and generative art, seems to agree. Speaking on her original concept of “machine imaginaire,” Molnár points out the role of chance in the generative art:

“[...] [As an artist] you are always having to make decisions. [...] With the machine imaginaire, there was a good tool for avoiding this — randomness. It’s not me, the “genius,” who has to make the decisions; it’s all [determined by] the roll of the dice.”

As an artist who often makes algorithmically generative work, I am particularly drawn to this process of “rolling the dice.” As software-driven methods of surveillance and optimization increase, we are fooled into feeling like we have control over own choices. We can choose from an endless list of results in Google Maps for a “coffee shop near me,” or sift through an infinite list of links to buy “baby blue ballet flats.” We can spend hours searching and scrolling in an attempt to exert agency over our frenzied, human lives. Despite these available methods of control, when engaging with big software platforms, who is truly using who?

In his essay in Real Life (also RIP) “I Write the Songs,” Rob Horning points out that algorithms “don’t reflect existing needs or wants; they are a system for instilling new ones.” Full agency remains a fantasy given that the algorithms we use daily are optimized to benefit the company behind its code. I’m Feeling Lucky resisted this illusion of choice that plagues our current state of being. She embraced the idea of luck and chance. She affirmed a belief in software’s ability to take you somewhere new by proposing just one unexpected thing.

I’m Feeling Lucky (My Version)

To honor I’m Feeling Lucky’s commitment to chance, luck, and software, I titled my most recent exhibition and generative collection after her. I’m Feeling Lucky, presented by the exhibition platform Verse, focuses on the relationship between randomness and astrology in contemporary internet culture. When I moved to Los Angeles in 2021 to pursue my MFA, I became hyper attuned to the presence of the stars. I learned I’m a Leo sun, Sagittarius moon, and Virgo rising. I downloaded apps that fed me my daily horoscope in a series of push notifications. Although I have always been a skeptic, in that moment I found relief in absolving myself of agency and letting something outside of my own mind tell me who I really am.

![The I’m Feeling Lucky exhibition at Verse’s physical space. [A white cube gallery with several black posters with white text and images.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fxq10wb7ogoji%2F1oCEYWleev8ySsju0ySB7Y%2Fc5fcea5c412e2f4a5a4cb49b9f7221ec%2FImFeelingLucky_SEPT23_006.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

In his book The Stars Down to Earth, Theodor Adorno argued that astrology appeals to “persons who do not any longer feel that they are the self-determining subjects of their fate.” Adorno, too, moved to Los Angeles and became enamored with the California culture industry. Though I possess a more indulgent relationship to pop culture than he did, his perspective resonates with my own creeping cynical feelings about both astrology and being online today. Realistically, astrology apps push content generated primarily through a combination of code and chance, not the stars. Despite this, the promise of prediction tugs at our neoliberal instinct to reclaim individual agency, appealing to someone who desires to feel a semblance of sovereignty amidst the often structurally-imposed challenges of our day to day lives.

But I wonder about the role of astrology for someone who is “in on the joke” — someone who knowingly engages with its practices while still harboring a healthy dose of skepticism. If someone finds online astrology “content” meaningful, does acknowledging the randomness of its source invalidate the weight of its meaning?

This is the question that drove me to write the algorithm that produced I’m Feeling Lucky. Remixing a library of words and phrases sourced from vintage astrology books, horoscope websites, and apps like Co-Star and The Pattern, I’m Feeling Lucky generates outputs that act as randomized “readings.” I was drawn to the idea that someone might see one of these pieces and think, that is totally me, effectively assigning meaning to something despite the known role of chance at play in the program.

![I’m Feeling Lucky #133. [A black background with white text that reads “You are Normal, Energized, Cheap, Unique,” all in various fonts. Stars, flowers and other small symbols adorn the image.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fxq10wb7ogoji%2F5cdzK0ZULzRpf1qti0DLRc%2F125ddd5546dfb5f5d67ef585bdc5a1a8%2Fimage1.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

![I’m Feeling Lucky #270. [A black background with white script that reads “You may be tempted to indulge in an extreme phone.” A similar style as the first image, but with no ornamentation.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fxq10wb7ogoji%2F5Vad21sq8AEqlVQ07wN18n%2Ff1a5a03758ec5293f8a59719e9a9a31f%2Fimage2.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Following the physical exhibition, Verse released an online version of the algorithmically generative collection on its website. For this, I wanted to clearly link I’m Feeling Lucky’s role in the story of Google Search to the role of chance in contemporary astrology, so I designed my own version of the button to be a part of the minting experience. During the auction, when someone went to collect an edition, the “Place Bid” button would change to read “I’m Feeling Lucky.” Those who secured an I’m Feeling Lucky edition with their bid were randomly assigned a single visual output.

![Place Bid to I'm Feeling Lucky button. [A gif showing a field for inputting your bid and a black and white button that says “Place Bid“ at first, but then “I’m Feeling Lucky’ when you hover the mouse over it.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fxq10wb7ogoji%2F1Ek7cYhsFWF9qTPamjI9yK%2F14ab9ab68868f851347dd0b2dd0e2d63%2FPlaceBidLuckyButton.gif&w=3840&q=75)

In his book Mythologies, Roland Barthes calls astrology a “confirmation of the real.” When my dad bid, he received a piece that says, “Your Personality Number is 7.” Seven has been his favorite number since he was a kid. Others shared out their randomized results on twitter, claiming the generated statements with a “yup it me!” or “i feel seen! 💗” I think reading one’s horoscope, whether generated by software or the stars, produces a similar feeling to clicking the I’m Feeling Lucky button and getting exactly you desired.

In the wake of I’m Feeling Lucky’s passing, I urge you all to hold her legacy in your hearts and minds. Consider how you felt about the internet when you first met her and how it’s changed since she left us. How can you “roll the dice” when navigating the internet today? How might “feeling lucky” change the meaning you find in the words and numbers that appear on your phone? In her memory, let us not only mourn her death, but celebrate her spirit. I’m Feeling Lucky, thank you for believing in the power of serendipity and spontaneous exploration online.

To us, you were a feature, not a bug.

Thank you. Please leave a flower to remember her below.

A poem for her (Excerpt from “Lucky Star” by Madonna)

You must be my lucky star 'Cause you shine on me Wherever you are I just think of you And I start to glow And I need your light And baby you know Starlight, star bright First star I see tonight Starlight, star bright Make everything alright Starlight, star bright First star I see tonight Starlight, star bright, yeah!